Growing numbers of people from the Horn of Africa have fled war and violence by immigrating to the United States. But although Ethiopians, Eritreans, and Somalis share borders and history, they also come from centuries of conflict that made them enemies to one another. Here in the Northwest, they often find themselves living together as neighbors, with their children meeting as classmates in school. In her new book 'Seeking Salaam: Ethiopians Eritreans and Somalis in the Pacific Northwest,' author and former University of Washington lecturer Sandra Chait brings us the voices of East Africans in the Pacific Northwest.

Growing numbers of people from the Horn of Africa have fled war and violence by immigrating to the United States. But although Ethiopians, Eritreans, and Somalis share borders and history, they also come from centuries of conflict that made them enemies to one another. Here in the Northwest, they often find themselves living together as neighbors, with their children meeting as classmates in school. In her new book 'Seeking Salaam: Ethiopians Eritreans and Somalis in the Pacific Northwest,' author and former University of Washington lecturer Sandra Chait brings us the voices of East Africans in the Pacific Northwest.

HS: What's your connection to East Africa?

SC: I used to teach African Literature at the University of Washington and I had this Eritrean friend who used to speak in glowing terms about her country. She'd tell me how everyone had worked together, united, to bring the country to independence and how they were working together yet again to develop Eritrea. There was no homelessness there, she said, no beggars on the street, and unlike in many African countries, the government wasn't corrupt.

Sandra Chait Sandra Chait |

She persuaded me and two colleagues to go out there and see for ourselves, which we did. At the time, 2001, we were incredibly impressed—things have changed since then – but then we were impressed enough that we formed a partnership between the University of Asmara and the University of Washington. We worked with Asmara in different disciplines: computer science, nursing, and in my case literature.

HS: How did you get the idea for a book about –East Africans in the Northwest?

SC: I was teaching an online course with an Eritrean colleague from Asmara and my students were able to meet his students through the internet and interview them. As I got to know more East African students and people in those communities, I got interested in their history, and I noticed that often people from different countries, different ethnic groups and different religions would tell me about the same event, but the stories were different. They came to it with different, often contradictory, perspectives.

Competitors in the bicycle Tour of Eritrea in Asmara, courtesy of wikipedia Competitors in the bicycle Tour of Eritrea in Asmara, courtesy of wikipedia |

Because I had grown up in South Africa during the early apartheid era, I was not surprised that competing stories existed. Growing up there in the '50s and '60s I knew there were Zulu stories, –Xhosa stories, Afrikaner stories, British ones: all different versions of the same history. And I was very conscious that in South Africa, the Afrikaner government then held all the power so they were able to suppress the other stories. I could see the possibility of the same thing happening with the Ethiopian, Eritrean, and Somalis stories, so I thought I would record them and bear witness to all the different versions.

HS: So what's the Twitter 140-character version of 'Seeking Salaam'

SC: It's about competing stories and what happens when you are a refugee in America, in Seattle and Portland and you're living next to people who are your enemy, as it were, and whose stories contradict your own. Seeking Salaam means seeking peace.

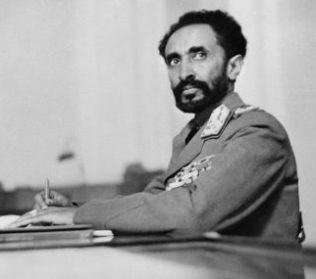

Haile Selassie Haile Selassie |

HS Why do the stories matter?

SC: I feel that stories and identity are very intimately connected so when somebody's story subverts your story it's really undercutting your whole identity. My book suggests that this subversion of identity is one of the challenges that face refugees beyond getting a job, education, and housing. Those obviously are the main challenges. But getting denied your history and identity is also a big deal.

So for example, if you are an Ethiopian and you are of the Amhara group, you would have been taught that your country's rulers belong to the royal lineage of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba through their son Menelik, who became the first emperor of Ethiopia. And you would learn that Haile Selassie was the 235th in that royal line from the House of David. So you hold yourself in a certain way with dignity because you have all this history behind you. But then an Eritrean says, 'Well actually, Menelik, the son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba was actually born where the city of Asmara is now and that's in Eritrea not Ethiopia. It's right by the river that runs through Asmara today'. Then a Somali says "Well, you know in those days before there were boundaries we were all one people, and who knows who slept with whom.'

HS: Who did you speak to for the book?

SC: I interviewed more than 40 men and women living in Seattle and Portland for the book. They were all over 20 and living in Greater Seattle and Greater Portland.

HS: What did you talk about?

SC: I went beyond polite protocol and I asked people what ethnicity they were, what clan they belonged to and so on. I wanted very much to have a variety of voices so I could get different viewpoints. I also spoke to people of different religions and different political persuasions. It's kind of a really mixed group. There were probably a few more people who were educated than not, but that's just the way it happened

I started off just asking them to tell me their stories. They nearly all eventually started focusing on the war years and the disputes.

HS: How do the stories affect these communities?

SC: Immigrants to America have all had to deal with competing stories. Just think about the Japanese, the Chinese; the English and the Irish; the Turks and the Greeks. But what makes it worse for these three groups is that the wars are still ongoing.

Somalia's a mess. Ethiopia and Eritrea are still –fighting proxy wars with each other. And the Internet makes it more difficult because anything that is going on back home, within a few minutes can be online here in this country. For those reasons, a lot of people in Seattle and Portland are caught up in the past. They can't let it go. And in some cases, especially among the older men, there is the notion that home is some kind of utopia. Maybe they were elders in the old country, but here they don't have that same status. They have perhaps lost dignity. So they tend to live in the past. They can't let it go and they can't reconcile with their past enemies.

HS: Is this also true for the younger people?

SC: Eventually the next generation starts dating the other group. The younger generation –is crossing those boundaries. They don't want to carry on with their parents antagonisms.

HS: Are people here worried about relatives back in Africa?

SC: Yes. One of the people who didn't want to have his name mentioned was someone who had family there. In Eritrea and Ethiopia, basically anyone who disagrees with the government is in danger. There is no freedom of speech. The newspapers have been closed down, and anybody can be put in prison. So you just have to be careful.

Somalia is a different situation because there is no stable government. Maybe that's why Somalis here were prepared to risk saying things. One of the Somalis that I interviewed, Koshin Mohamed, was actually a student advisee of mine who was made the ambassador designate to Somalia. And he was very outspoken. He said, for example, that Somalis hated Jews. But he then went on to explain that that was because they had been indoctrinated .

HS: Did any of the stories you heard surprise you?

SC: Yes numerous things. One woman told me of attempted rape. And another called the Somali president –Siyad Barre, who ruled from 1969 to 1991, a lying b****** who had destroyed the country. Granted, he is gone and doesn't have power any more but there are a lot of people who still support him. When I asked her 'Are you sure you want to say this?' she said, 'Yes! I'm absolutely sure.'

I found the Somali women in particular, very outspoken, very brave.

HS: Who's writing the history in Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia now?

SC: Among the Ethiopians that's the Tigre group. In Eritrea it's the Tigrinya. And in Somalia, well, there is a transitional federal government at the moment that has American support and is trying to repress al Shabaab which is an extremist Islamic group that has ties with alQaeda. But it's anyone's guess who ultimately will have control of the Word in Somalia.

HS: We have seen quite a bit of anti-Muslim sentiment. Is that difficult for these communities?

SC: Compared to some places, Seattle and Portland are both relatively tolerant cities. But even so I think that Muslims have had a really hard time here with stereotyping, especially since 9/11. Americans sometimes favor Ethiopians in the Horn because they assume that their country is a Christian bulwark against Islamic terrorism, but they don't always realize that Ethiopia is close to 50 percent Muslim; Eritrea as well.

So, yes, there is a lot of tension about it. I was very appreciative that the Muslims spoke openly to me. I was scared for them, and I actually said on some occasions, 'Are you sure you want to say this?' They said Yes.

HS: We've heard about a few Somali youth joining radical groups or getting into trouble. What did you hear about radicalized youth?

SC: Most of those came from Minneapolis not Seattle. And this wasn't happening at the same time that I was writing and interviewing. So, it wasn't something I discussed. Certainly, parents were concerned about their kids getting into crime of any sort. This is a major problem for all three communities. There were kids in juvenile detention and the parents just couldn't understand where they'd gone wrong.

HS: What are the challenges for the young people?

SC: It's difficult culturally. The young want to fit in with their peers, but at home their parents want them to live according to their culture. So they have to respect and obey their parents, and they can't say anything to disagree with them. East African parents have traditionally used corporal punishment on their children, but here if they try that their kids will phone the abuse line and report their parents, thus causing serious conflict between the generations.

HS: Does this story have a happy ending?

SC: What I want to emphasize is that although there are animosities and there are undercurrents going on all the time, there are many –East Africans who are seeking to reconcile and work together for the common good. There really are. Like earlier generations of immigrants, they are moving on. They are seeking peace and trying to work together so –their children don't have to carry this burden of hatred into perpetuity.

Map courtesy of the Alliance for Peacebuilding, which works in the Horn of Africa to reduce famine, violence and conflict.