WASHINGTON (AP) -- Fending off demands that he resign over the Abu Ghraib prison scandal, then-Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld told Congress in 2004 that he had found a legal way to compensate Iraqi detainees who suffered ``grievous and brutal abuse and cruelty at the hands of a few members of the United States armed forces.''

WASHINGTON (AP) -- Fending off demands that he resign over the Abu Ghraib prison scandal, then-Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld told Congress in 2004 that he had found a legal way to compensate Iraqi detainees who suffered ``grievous and brutal abuse and cruelty at the hands of a few members of the United States armed forces.''

``It's the right thing to do,'' Rumsfeld said. ``And it is my intention to see that we do.''

Six years later, the U.S. Army is unable to document a single payment for prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib.

Nor can the more than 250 Iraqis or their lawyers now seeking redress in U.S. courts. Their hopes for compensation may rest on a Supreme Court decision this week.

The Army says about 30 former Abu Ghraib prisoners are seeking compensation from the U.S. Army Claims Service. Those claims are still being investigated; many do not involve inmate abuse.

The Army said that U.S. Forces-Iraq looked at its records and could not find any payments to former detainees. The Army also cannot verify whether any such payments were made informally through Iraqi leaders.

From the budget years 2003 to 2006, the Defense Department paid $30.9 million to Iraqi and Afghan civilians who were killed, injured, or incurred property damage due to U.S. or coalition forces' actions during combat. The Army has found no evidence any of those payments were used to compensate victims of abuse at Abu Ghraib.

So instead of compensation, the legacy of the most infamous detainee abuse episode from President George W. Bush's tenure is lawsuits, and the court battle mirrors the Iraq war -- a grinding, drawn-out conflict.

At the U.S. Supreme Court, the former detainees are asking the justices to step into a case alleging that civilian interrogators and linguists conspired with soldiers to abuse the prisoners. All the detainees, who allege they were held at Abu Ghraib or one of the other 16 detention centers in Iraq, say they were eventually released without any charges against them.

Their case presents a fundamental legal issue: Can defense contractors working side by side with military jailers be sued for claims arising in a war zone?

Their case presents a fundamental legal issue: Can defense contractors working side by side with military jailers be sued for claims arising in a war zone?

The U.S. government is immune from lawsuits arising from combatant activities of the military during time of war.

The ex-detainees are suing CACI International Inc. of Arlington, Virginia, and L-3 Services Inc. of New York, formerly called Titan Corp. of San Diego. Both companies say the suits fail to link any of their employees to abuse.

The Supreme Court considers the case in private Monday and could announce as early as Tuesday whether it will take the case.

``It's really outrageous that there hasn't been a widespread commitment to compensate the clear victims of this abuse, and it's extremely troubling that the government doesn't appear able to document any compensation for victims whatsoever,'' said Vince Warren, executive director of the Center for Constitutional Rights, a private group overseeing lawsuits against the civilian contractors since 2004.

``The U.S. government seems to have failed miserably in securing at least one portion of the accountability for these actions,'' he said.

Although the U.S. military used signs, pamphlets, broadcasts and word of mouth to let the Iraqi public know how to make claims against U.S. forces, ``very few claims appear to have been made'' related to Abu Ghraib inmate abuse, Lt. Col. Craig A. Ratcliff, an Army spokesman, told The Associated Press.

``We believe there could be several reasons for this, including the cultural and social stigma of having been detained or mistreated that could be a source of embarrassment preventing a former detainee from coming forward,'' he said.

Ratcliff said that just 31 requests for compensation filed with the U.S. Army Claims Service ``could involve possible detention at Abu Ghraib'' and that many of the 31 involve allegations such as missing cash and lost personal items rather than physical abuse. All 31 ``are pending investigation and action.''

Two views of Abu Ghraib abuse

The detainees' allegations and Rumsfeld's testimony on Capitol Hill on May 7, 2004, offer conflicting views of what took place at Abu Ghraib.

The suits, which seek unspecified compensatory and punitive damages, allege that four prisoners died at Abu Ghraib from beatings and that employees of the defense contractors, U.S. soldiers, or both, were responsible. Among the hundreds of allegations in the cases:

_While detained at Abu Ghraib, two sisters were forced by their captors to witness their detainee brother being beaten so severely he died of his injuries several days later.

_A young prisoner at Abu Ghraib was forced to watch his detainee father being beaten with guns in the head, back, stomach and genitals days before he died of those injuries.

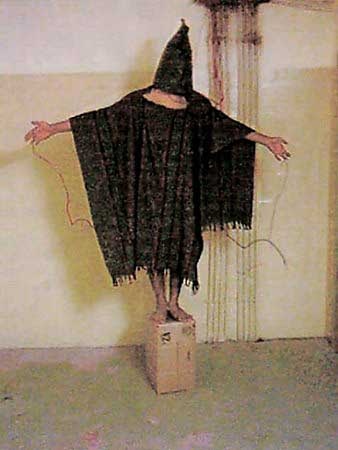

In contrast, Rumsfeld's testimony about compensation was based on graphic photographs leaked to the news media showing abuse inflicted on a relatively small number of detainees during the night shift along Tier 1 at Abu Ghraib from September to December in 2003.

Sworn statements by 13 Abu Ghraib inmates which U.S. Army investigators found credible form a key piece of the first public U.S. military report in 2004 on what took place at the prison. At the time, Abu Ghraib was the largest detention facility in Iraq, with 7,000 inmates.

One detainee told investigators that his jailers ``beat me so bad I lost consciousness for an hour or so.'' A second prisoner said his assailant ``started beating me with the chair until the chair was broken. After that they started choking me. ... I thought I was going to die.''

A military investigation later in 2004 identified 44 alleged incidents of detainee abuse at Abu Ghraib.

``The practices that took place in that prison are abhorrent and they don't represent America,'' Bush said.

Eleven U.S. soldiers were convicted of crimes at Abu Ghraib ranging from aggravated assault to taking pictures of naked Iraqi prisoners being humiliated. Five officers were disciplined.

One Army investigation found that three employees from CACI and one from Titan _ their names were withheld by the military _ more likely than not engaged in abuse at Abu Ghraib. No employee from either company was charged with a crime in investigations by the U.S. Justice Department. Nor did the U.S. military stop the companies from working for the government.

U.S. courts disagree over claims

Regardless of whether the detainees' allegations or the Bush administration's limited view of the abuses is more accurate, the suits underscore a basic reality of the Iraq and Afghan wars: Tens of thousands of civilian contractors work closely with soldiers.

That closeness underpins the Abu Ghraib suits, but there are conflicting court rulings on whether U.S. law protects the contractors as well as the government from suits.

The Supreme Court often resolves disagreements between lower courts, but it's far from certain the justices will step into the Abu Ghraib cases now.

They could adopt the Obama administration's view, expressed four months ago in a case unrelated to prisoner abuse, that the whole issue of liability of private contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan ``would benefit greatly from further percolation'' in the lower courts.

In the case the justices are being asked to review, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit dismissed the detainee suits against CACI and Titan a year ago by a 2-1 vote.

Like Rumsfeld, two of the appeals court judges pointed to the U.S. Army as the place to go for compensation.

``The U.S. Army Claims Service has confirmed that it will compensate detainees who establish legitimate claims for relief under the Foreign Claims Act,'' wrote appeals judge Laurence Silberman. Therefore, the detainees ``will not be totally bereft of all remedies for injuries sustained at Abu Ghraib,'' added Silberman, an appointee of President Ronald Reagan. Silberman was joined by appeals judge Brett Kavanaugh, a George W. Bush appointee.

The dissenting judge, Merrick Garland, said detainees have no legal rights under the Foreign Claims Act. That law ``merely authorizes designated officials to make _ or not make _ certain payments as a matter of their unreviewable discretion,'' wrote Garland, an appointee of President Bill Clinton.

Six months before the appeals court ruling in Washington, a federal judge in Alexandria, Virginia, ruled that four former Abu Ghraib inmates can sue CACI for alleged abuse. That case is now in the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond.

- Home

- News

- Opinion

- Entertainment

- Classified

- About Us

MLK Breakfast

MLK Breakfast- Community

- Foundation

- Obituaries

- Donate

11-05-2024 8:36 am • PDX and SEA Weather